Leisler’s bat (Nyctalus leisleri) is the largest species of bat in Ireland.

It was first reported as an Irish species by Professor Kinahan to the Belfast Natural History and Philosophical Society in 1860. It was not ascertained to be a plentiful species in Ireland until, in 1868, R.M. Barrington discovered Leisler’s bats in large numbers inhabiting hollow beech trees in woods in the Duke of Manchester’s demense at Tandragee, Co. Armagh. Leisler’s bat was known then as ‘the hairy-armed bat’ due to its fur extending thickly onto the wing membrane and along the forearm.

Leisler’s bat is easily identified. One of the main diagnostic features is the distinctly bi-coloured fur. Individual hairs are darker towards their bases, with lighter tips. The colour of the fur ranges from golden to dark rufous brown. In addition, there is a very distinctive short, mushroom-shaped tragus in the ear and a prominent post-calcarial lobe.

The echolocation call is very distinctive, consisting of two distinct elements, and it peaks at a frequency of 24-28KHz. It is a very loud call which can be picked up at a range of c.100m on a bat detector.

Leisler’s bat is an exclusively aerial-hawking species – all its food is caught and eaten in flight. It takes mainly small and medium-sized insects, many from swarms. The diet consists of mainly yellow dungflies, craneflies, beetles, moths and insects with aquatic larvae (mayflies, caddis flies, midges). Leisler’s bats forage in a variety of habitats including over pasture, rivers, lakes, canals, forestry and around streetlights/flood lights.

Maternity colonies form in late spring/early summer, mainly in buildings but also occasionally in hollow trees. Hibernation records are scarce but most are from hollows and crevices in trees.

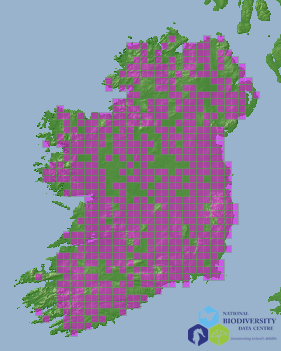

Distribution

The world distribution of Leisler’s bat stretches from western Europe to southern Asia, and also found in northwestern Africa. It is distributed throughout Europe except Iceland, Scandinavia, Estonia and northern Russia. Ireland is generally considered to be the stronghold of its world distribution. Leisler’s bat is widely distributed throughout Ireland.

Roosts

In Europe, Leisler’s bat is considered to be essentially a forest bat, roosting in tree holes and bat boxes. However, in Ireland, nursery roosts are chiefly located in attic spaces of buildings. There are also a few records of nursery roosts in trees. Nursery roosts of up to 100 adult females are relatively common. The position of such roosts is often advertised by loud vocalisations by the bats before emergence at dusk.

When nursery roosts break up in August, adult females move to ‘transitional’ roosts, mainly in trees. By late August/September all bats remaining in the nursery roost are juvenile bats born that year. There are very few records of hibernacula from Ireland but Leisler’s bats have been recorded hibernating in tree hollows of mature deciduous trees, and occasionally in buildings.

In continental Europe Leisler’s bat is considered to be a migratory species with several long distance movements being recorded. Leisler’s bat does not migrate from Ireland.

Reproduction

Adult females begin to congregate in nursery roosts from April onwards. Females give birth to a single young between mid and late June. Not all females reproduce every year. Young females may mate and give birth within their first year. The young are capable of flight within approximately 30 days. Mating commences in late July/August. Male Leisler’s bats emit ‘mating-calls’ while sitting stationary on tree trunks. This is a clearly audible call which is repeated approximately every second. The timing of pregnancy and birth the following spring is controlled by a process termed ‘delayed fertilisation,’ where sperm is stored separately over winter in the female’s body until weather conditions are favourable.

Foraging

Leisler’s bat emerges relatively early, often before sunset. It commutes at high speed, at heights of up to 100m, directly to their selected foraging grounds. This commuting flight is generally straight with occasional shallow dives. Actual foraging has been observed at heights between 1m and approximately 30m and has more turns and dives. Foraging is unaffected by drizzle or light rain but during spells of heavy rain/showers bats return to roost.

Radio-telemetry studies have revealed that Leisler’s bat forages over a range of habitat types including over cattle/sheep pasture, rivers, lakes, canals and forestry. It also hunts around streetlights and floodlights for insects that are attracted to artificial light. Foraging is generally not continuous throughout the night in the period before the young are born. During this period, activity patterns are either unimodal or bimodal with all bats taking their main foraging flight at dusk, but the occurrence of a shorter flight towards dawn is temperature dependent. The timing of these foraging flights is thought to coincide with the flight patterns of insect prey. However, during lactation, activity becomes multimodal, with lactating females taking up to five flights per night as they return regularly to the roost throughout the night to suckle their young.

Leisler’s bats have long narrow wings and display high-speed agility but limited manoeuvrability. This wing shape enables fast, energetically-economical flight, suitable for rapid dispersal to distant feeding grounds.

Leisler’s bats swarm outside the nursery roost site prior to entering it at dawn.

Genetics

Examination of the genetic diversity in Irish populations of Leisler’s bats, in the context of Europe, revealed an interesting history of two colonisation events after the last glaciation. In Ireland, two distinct genetic groups co-occur, and similarly in Britain, leading to high levels of genetic diversity in both localities. One group has a distribution across Europe, while the other is found only in the Azores Islands, with Ireland and Britain acting as a hybrid zone between the two genetic groups. These groups are likely to have diverged in different glacial refugia, however, are not so dissimilar so that they do completely intermix within Ireland and Britain with maternity colonies containing females of both historical groups. This, along with the fact that Ireland has the largest population of this species in Europe, makes them of particular conservation importance.

Examination of the distribution of genetic diversity within Ireland revealed that Leisler’s bats represent a single population with no geographic barriers to movement across the island.

Conservation Status

In Ireland’s most recent (2009) Red List of terrestrial mammals published by the National Parks and Wildlife Service the conservation status of Leisler’s bat is classified as Near Threatened in Ireland. The population in Ireland is thought to be stable and is estimated to comprise 20,000+ mature individuals. This species is protected under the Wildlife Act (1976) and Wildlife (Amendment) Act 2000.

However, a recent survey (2011) by Bat Conservation Ireland of all known traditional nursery roosts of Leisler’s bats in the Republic of Ireland and a selected number of sites in Northern Ireland revealed that this species is no longer present at a high proportion of these sites. In some cases the bats were excluded deliberately, while in others cases it was accidental. Roost buildings had also been demolished.

The recent colonisation of Ireland by the great spotted woodpecker (Dendrocopus major) may increase the availability of roost sites in trees for Leisler’s bat.

Threats

The main threats to this species include exclusion from nursery roost sites and the use of unsuitable remedial timber treatments in attic spaces. Unsympathetic tree surgery and tree-felling may reduce the availability of suitable roost sites. Mature deciduous species are particularly important for Leisler’s bat.

The widespread use of the antihelmintic drug Ivermectin in cattle may have negative implications for the foraging success of this species, given the importance of pastoral prey in their diet.

Caroline Shiel and Emma Boston

Caroline attended University College Galway where she obtained her BSc in 1989, during which she undertook a study of the diet of four species of Irish bat by faecal analysis. She then returned to UCG to undertake a PhD on Leisler’s bat, titled Diet, foraging and activity at the roost of Leisler’s bat (Nyctalus leisleri) with special reference to nursery colonies in south Co. Wexford, Ireland, which she completed in 1998. Since then Caroline as been working as a ecological consultant specialising in bats and running an on-line antiquarian book shop Owl Books.

Emma Boston is a molecular ecologist with broad interests in vertebrate ecology, evolution and behaviour. She completed her PhD at Queen’s University Belfast on Leisler’s bat (Nyctalus leisleri) populations in Ireland and Europe, examining phylogeography, population genetics and social structure. While working at the Centre for Irish Bat Research, her research focused on assessing the use of non-invasive samples to the study of population genetics in bats and developing a reliable method for continuous population monitoring of these rare species with non-invasive techniques.

Selected Publications and Reports

- Boston, E.S.M., Montgomery, W.I., Hynes, R. & Prodohl, P.A. (2015) New insights on postglacial colonization in western Europe: the phylogeography of the Leisler’s bat (Nyctalus leisleri). The Royal Society: Proceedings B.

- Boston, E.S.M., Roue, S.G., Montgomery, W.I., & Prodohl, P.A. (2012) Kinship, parentage and temporal stability in nursery colonies of Leisler’s bat (Nyctalus leisleri). Behavioural Ecology. DOI 10.1093/beheco/ars065.

- Boston, E. S. M., Montgomery, I. & Prodöhl, P.A. (2009) Development and characterization of 11 polymorphic compound tri- and tetranucleotide microsatellite loci for the Leisler’s bat, Nyctalus leisleri (Vespertilionidae, Chiroptera). Conservation Genetics: 10: 1501-1504.

- Boston, E.S.M., Buckley D., Bekaert M., Lundy M. G., Gager, Y., Scott D.D., Prodohl, P.A., Montgomery, I., Marnell, F. & Teeling, E. (2010) The status of the cryptic species, Myotis mystacinus (Whiskered bat) and Myotis brandtii (Brandt’s bat) in Ireland. Acta Chiropterologica,12(2): 457–461.

- Boston E.S.M. (2010) A size comparison of Irish Leisler’s Bats (Nyctalus leisleri Kuhl, 1818) with those in continental Europe. Irish Naturalist Journal, Zoology Note, 31 (1).

- Boston E.S.M, Roue S.G., Montgomery W.I. & Prodohl P.A. (2012) Kinship, parentage, and temporal stability in nursery colonies of Leisler’s bat (Nyctalus leisleri), Behavioral Ecology 23(5): 1015-1021.

- Shiel, C.B. (1999) Bridge usage by bats in County Leitrim and County Sligo. Heritage Council, Kilkenny.

- Shiel, C.B. & Fairley, J.S. (1999) Evening emergence of two colonies of Leisler’s bat (Nyctalus leisleri) in Ireland. Journal of Zoology 247: 439-447

- Shiel, C.B., Shiel, R.E. & Fairley, J.S. (1999) Seasonal changes in the foraging behaviour of Leisler’s bats (Nyctalus leisleri) as revealed by radio-telemetry. Journal of Zoology: 249: 347-358.

- Shiel, C.B. & Fairley, J.S. (1999) Evening emergence of two colonies of Leisler’s bat (Nyctalus leisleri) in Ireland. Journal of Zoology 247: 439-447.

- Shiel, C.B., Duverge, P.I., Smiddy, P. & Fairley, J.S. (1998) Analysis of the diet of Leisler’s bat (Nyctalus leisleri) in Ireland with some comparative analyses from England and Germany. Journal of Zoology 246: 417-425.

- Shiel, C.B. & Fairley, J.S. (1998) Activity of Leisler’s bat Nyctalus leisleri (Kuhl) in the field in south-east County Wexford, as revealed by a bat detector. Biology and Environment 98B: 105-112.

- Shiel, C.B., McAney, C.M., Sullivan, C.M. & Fairley, J.S. (1997) Identification of arthropod fragments in bat droppings. An occasional publication of the Mammal Society, London. Number 17.

Key information

English name:Leisler’s bat

Latin name:Nyctalus leisleri

Irish name:Ialtóg Leisleri

Identifying feature:Short, mushroom-shaped tragus; bi-coloured fur.

Number of young:1 pup, born mid to late June.

Diet:Small to medium-sized swarming insects, caught exclusively in flight.

Habitat:Nursery roosts in buildings (both inhabited and uninhabited) and occasionally trees; Winter roosts in trees. Forages mainly over pasture, waterbodies and around streetlight/floodlights.